Utterly fascinating article:

Church 26 – Emmanuel Baptist Church

I was less of an ‘outsider’ this week, as I’ve visited Emmanuel a number of times, and know quite a few members of the church. In general I’ve also heard the church spoken about favourably by others around the city.

I was less of an ‘outsider’ this week, as I’ve visited Emmanuel a number of times, and know quite a few members of the church. In general I’ve also heard the church spoken about favourably by others around the city.

The first thing I noticed about Emmanuel is how incredibly well organised it was. Everyone, from the parking attendants to the Sunday school workers to the sound engineers were doing their job with a practiced efficiency. The service finished with a heartfelt extemporaneous prayer exactly one hour and ten minutes after it started. The audio-visual were flawlessly executed, the musicians landed their openings perfectly, and the congregation sang enthusiastically and on-key.

The second thing I noticed about Emmanuel was its use of carefully controlled emotionalism. The entire service is engineered to elicit a certain emotional reaction. Writing this a week later I remember far more about the delivery of the sermon than the content. I recall that the subject was Paul’s letter to the Colossians but I remember much more about the preacher’s style.

He told moving stories. He showed us a picture of a truck nearly falling down a canyon. His voice rose and fell, sometimes he was warm, sometimes impassioned. He called us ‘friends’ a lot. He came out from behind the lectern and reached out a hand to the audience, urging us to accept his point.

And, as far as I could tell, the whole congregation was listening with rapt attention.

It’s at times like this that I realise that I don’t really get evangelicalism. Part of my goal during this journey is to understand the church in Barrie, and this requires understanding her practices. Pretty much every church I’ve been to does the following:

- Sing together.

- Drink Coffee.

- Some form of prayer.

- Listen to a sermon.

Sometimes other rituals such as communion or confession are included. Now, to a certain extent I understand the sacrament of communion. My spirit is refreshed and I leave the Eucharist feeling like I’ve encountered some of God’s grace. And I find myself wondering if the sermon is something of an evangelical sacrament. Just as it wouldn’t be a catholic Mass without communion, perhaps it’s not a proper evangelical service without a sermon.

It’s clear to me that the point of a sermon, however, is not education. A university lecture is accompanied by textbooks, tutorial groups, practical sessions and tests, and operates in conjunction with these other teaching tools. Furthermore, it’s structured – you know before you start a course what the curriculum is, what the prerequisites are, and generally you choose your subjects based on your interests or goals.

But I’ve yet to see a church where the sermon curriculum is published so congregants can see which ones they can skip because they’ve already covered the material. Furthermore there’s little allowance made for the self-directed learner, who might want to read the material rather than listen to it, or remedial classes for those that are struggling with the material, or any evaluation mechanism to determine whether students are grasping the topic.

So I’m left with the conclusion that a sermon is about inspiration, not information.

Given the near-ubiquity of this style of doing church, this must be what a large number of people actually want. Maybe for most people listening to this style of motivational, inspirational speaking for 45 minutes every Sunday makes them feel better prepared for their week, more focused, or more connected to God?

I want to understand this dynamic as I try to understand the church in Barrie. So help me out! If you’re a regular churchgoer, tell me why the sermon is an important part of your church experience. Let me know why it appeals to you, and what you feel its benefits are. Is it an essential element of church, or just an important one?

I look forward to hearing your thoughts!

Galileo

If we are looking for a classic example of the conflict between modernism and pre-modernism, we need look no further than the Galileo affair. The conflict between Galileo and the church authority dramatically illustrates the tension between two different ways of assessing ‘truth’.

It’s a fascinating story with all the elements of a gripping novel. Colorful personalities, political intrigue, the misunderstood genius facing down powerful forces arrayed against him, and culminating in a thrilling courtroom drama.

It’s a fascinating story with all the elements of a gripping novel. Colorful personalities, political intrigue, the misunderstood genius facing down powerful forces arrayed against him, and culminating in a thrilling courtroom drama.

In 1616 Galileo was ordered to stand trial for heresy by the Inquisition. He was accused of ‘having held the opinion that the Sun lies motionless at the centre of the universe, that the the Earth is not at its centre and moves, and that one may hold an opinion as probable after it has been declared contrary to Holy Scripture.’

Galileo held his position because of the observations he had made through his telescope. His accusers did not need to look through a telescope themselves to prove him wrong; because their conception of Truth was different. They needed instead to appeal to authority. Their scriptures indicated that the Earth was stationary, and the Pope had banned Galileo’s book. Therefore the matter was clear. Galileo was guilty.

This trial was not really about Galileo, or about telescopes or astronomy, but about worldviews. Was Truth something to be acquired by observation, or by declaration? Were people to trust their senses or trust their leaders? And when the two came into conflict, which side would dominate?

Galileo lost his trial, and was sentenced to house arrest for the rest of his life. But this was the beginning, not the end, of the modern era. Other challenges to Revealed Truth would soon arise. The idea that authoritative truth claims could be questioned, tested, and even rejected if they failed to match up to observed facts would rapidly spread.

Church 25 – Calvary Community Church

This morning’s church was Calvary Community Church, located just outside the city limits on 5/6 sideroad.

This morning’s church was Calvary Community Church, located just outside the city limits on 5/6 sideroad.

I’ll get straight to the point – I liked this one. There are quite a few things that this church is getting right.

In no particular order, then:

I liked the decor. The outside is ‘classic North-American church’, with pillars and a spire, but the inside felt more like a nicely decorated house.

I liked the mix of people. There was a good range of ages and backgrounds represented this morning.

This might be my personal bias showing, but I liked the Pentecostal feel. The worship was heartfelt and led by a competent group, and the congregation felt quite happy responding with a lot of ‘Yes, Lord‘s and ‘Amen‘s.

The sermon lasted the best part of an hour, and I even liked that. It’s not that common to find a speaker who can take quite a lot of theological material, deliver it in a very accessible fashion, and manage to keep the whole message both cohesive and pastoral. I heard from my ‘agents’ in the Sunday School that the same material was covered during the children’s ministry. My agent was also pleased to report that her questions and contributions to the discussion were received respectfully, which has certainly not been the case in every church we’ve visited.

The message was anchored in Mark 11. In the Old Testament, God’s presence was found in a specific physical structure, the temple. But after Christ, his presence is now in humanity, enabling us to be God’s agents to one another, and for God’s ministry of reconciliation to work through us.

After the service it took a while to find someone to talk to; like many close-knit churches visitors can easily feel like outsiders. But I did get to ask my standard questions about both this particular congregation and God’s work in the city. This church, I was told, is learning to be more outward focused; learning to move into the community rather than expect the community to come to her. Furthermore, I got a strong sense of a desire to serve the city in both spiritual and practical ways.

This is definitely a common theme I’m seeing in nearly every church I visit. Regardless of the specific ministries they are engaged in, there seems to be an awareness that the church in Barrie is being called to serve the city, and especially the under-privileged, in gracious, practical ways.

——

Finally, I found the video that was used to start the service pretty funny:

Church 24 – Bethel Community Church

So, if last week’s experience left me feeling a little like an outsider, my visit to Bethel Community Church this week was the complete opposite. I’m sure at least 10 people introduced themselves to me or my wife and welcomed us to the church. This is definitely one of the friendliest congregations in town. We even got to meet some readers of this blog, who had some very complimentary comments to make.

As an aside, my goal here isn’t to create an official ‘church directory’ for Barrie, but I expect that when I’m done this will become one of the most comprehensive descriptions of the congregations in the city.

The service at Bethel was another fairly typical Evangelical one. The usual pre-service music, opening songs, greetings and announcements, and then what I thought was the sermon.

The service at Bethel was another fairly typical Evangelical one. The usual pre-service music, opening songs, greetings and announcements, and then what I thought was the sermon.

As it happens, Bethel likes its sermons, and generously provides several of them during the morning. First we had a kids-oriented discussion about communion. Unlike most Anglican churches where children are brought into the service from Sunday school to take communion, at Bethel they get given a talk and then sent out before it starts. And whereas some churches I’ve visited have emphasized communion as a celebration of our participation in God’s family, the focus here was on encouraging the children to ‘make a decision for Christ’ at some point in their later lives.

After the kids were dismissed we had the second sermonette of the day, again about communion but this time focusing on the need for reconciliation with each other before we seek reconciliation with God. I liked this bit; the speaker urged the congregation to take time, even during the service, to seek out others with whom they had disagreements before they ate together.

After communion another guy got up to give what I thought were going to be closing remarks, but actually turned out to be the main sermon. The subject was ‘tithing’, and I’ve already reflected a little on this talk here.

Finally, just in case we didn’t get the point, after the last song yet another leader stood up to give a mini-message re-iterating the main speakers point.

Bethel is currently in between pastors, and so going through all the usual pastoral search committee fun that that entails. This also means that a visit now may not be 100% representative of what the church would feel like in six months time – pastors like to stamp their character on a church fairly soon when they arrive in my experience.

I’d heard good things about Bethel from other folks in the city before I visited, and my impressions were of a warm, friendly, welcoming congregation that’s in the middle of a transitional phase. I wish them all the best as they figure out the direction they are going in.

And God said “Are the Steaks Ready Yet?”

So, yesterday I was treated to what I like to call the Basic Evangelical Tithing Sermon, or BETS. You’ve probably heard it yourself a few times, if you’ve moved in evangelical circles. Many churches will trot it out once a year or so. It tends to annoy me, because it tends to conflate a quite reasonable review of the church’s financial situation with a bundle of guilt and some really bad hermeneutics.

I was going to write an angry point-by-point refutation of the BETS, but a cooler head than mine suggested otherwise.

So instead, a brief thought on the subject of tithes.

If we’re going to talk about tithing, then we can’t really avoid Deutronomy Chapter 14, where the Israelites are instructed by their God that it was their sacred duty to have the mother of all barbecues every year.

I’m serious. Go read it.

It’s a fascinating chapter. The first third is all about the importance of finding a good Kosher supermarket in your neighbourhood. The last paragraph is about how it’s a good idea to take care of those on the edge of society: the immigrant, the orphan, the single parent. And in the middle section of the chapter the Israelites are explicitly commanded to to spend one tenth of their yearly incoming on “cattle, sheep, wine or beer” or anything else that they liked, and eating together in one big annual party.

A tenth of your household income. Maybe 5 or 6 thousand dollars for a typical Canadian family. On a barbecue. That’s a lot of steak and Molsons! And this isn’t just a backyard get-together, the entire country was supposed to get in on this. It makes Burning Man sound kinda tame.

Apparently, when God talks about tithing, he talks about barbecues.

Church 23 – Collier St. United

Collier St. United is another of our larger downtown churches, steps away from the bar and shopping district on Dunlop street.

Unlike Painswick United, a small congregation meeting in a strip-mall, Collier Street has a large facility that it uses to the max. The main sanctuary on Sunday was packed, and the balcony was mostly full too.

Collier Street strikes me as a very ‘involved’ church. During the service, an ‘Installation of Officials’ was held; a recognition and commissioning of those serving the church in various capacities this year. 25 or 30 people came to the front for this part of the service. In fact, there’s clearly tons of activity going on here. There were 60 or so events listed for this week alone on the handout sheet, and judging by the announcements, the church website, and the various bulletin boards around the building, Collier Street should win the award for ‘Church in Barrie with the Most Programs.’

The service itself followed a typical format; songs, announcements, performances by two different choirs, and a sermon. Interestingly, although the topic of the sermon was Christ’s passion, the Rev. Dennis Posno chose to talk about Jesus’ life, not death, about Jesus’ passion for peace, for hope, for justice and for healing.

Collier Street is clearly a tight knit community, and like some other similar churches, it can be very easy for a visitor to be aware of their status as an outsider. At First Christian Reformed, 4 or 5 people introduced themselves to me and welcomed me to the service before it had even started. At Collier Street no-one really noticed my presence, despite the convivial atmosphere at coffee hour. This is a tricky balance for any church to strike, between nurturing its existing community and being open and welcoming to outsiders. But that said, I think if someone did take the time and effort to get involved, they would find it a warm and accepting community.

Francis Bacon

If we are going to discuss modernism and postmodernism, then we should really also briefly cover pre-modernism. If the postmodernist looks to their social network for authority, and the modernist looks to the expert, then the pre-modernist looks to the hierarchy.

The dramatic shift from pre-modern to modern thought has it’s roots, I think, in the Enlightenment. Francis Bacon (friend of Queen Elizabeth I and King James I, Attorney General, Lord Chancellor, lawyer, philosopher, author, scientist, and all-round overachiever), started his book “Novum Organum” with the following aphorism:

Man, being the servant and interpreter of Nature, can do and understand so much and so much only as he has observed in fact or in thought of the course of nature. Beyond this he neither knows anything nor can do anything.

In other words, we know about stuff we can experience.

Nothing particularly earth-shattering, perhaps, to the modern ear. But this was a terrifyingly subversive claim to make. To start with, he is directly challenging the institutional Church and her claims to divinely revealed truth. To the pre-modern, ‘truth’ is something that is received from the hierarchy. The peasant receives instruction from the priest, who in turn receives instruction from the bishop, who receives his instruction from the Pope, who’s wisdom comes via divine revelation straight from God.

But Bacon is saying “no, the only way we can know things is through empiricism; through direct experience, through our own senses and observations.” And the implications of this are clear. If the hierarchy claims one thing, but we observe a fact that contradicts their claim, then they must be in error.

We’ll see how this conflict between revealed truth and observed truth played out most clearly in my next article, when we turn our attention to Galileo.

Redacted.

Now this is fascinating.

Thanks to wikileaks, it is now possible to compare versions of some U.S. government documents that have been released under Freedom of Information Act requests, but in redacted form, with the actual raw documents themselves. Thus we can have an insight not only into the material the documents cover, but also what topics the government censors feel must be withheld.

http://www.aclu.org/wikileaks-diplomatic-cables-foia-documents

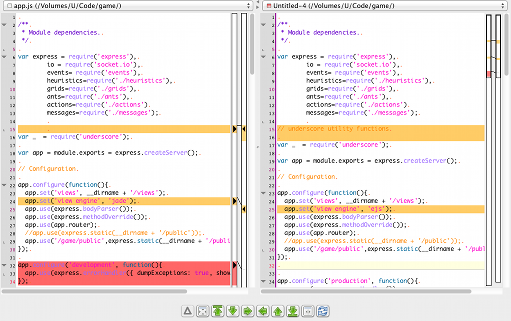

In software development, one of the most frequently used tools is something we call diff. A diff tool compares two versions of a text file, typically a design document or a the source code for a program, and highlights the changes between them. For the programmer, this is a useful tool to see what has changed between versions, to see if any errors have crept into the source, to see what modifications other team members may have made to the file, and to see how the code has evolved over time.

I have a feeling that in the future this technology will become more prevalent in the legal and governmental world. It will be possible to track all the changes on a government bill as it proceeds through the legislative process. Any attempt by a politician to make significant changes shortly before the bill is passed will become very obvious. In fact I hope that with the rise of this kind of tool, along with collaborative websites along the lines of Wikipedia, the Canadian population can become much more involved in understanding, reviewing and contributing to the legislative process.

Industrial Processes: Cars, Coffee and Conscripts.

I believe that one can trace a very logical historical path from the rise of modernism through to the development of postmodernism. However, I probably won’t keep these article in strict chronological order. Be prepared for me to hop and skip around!

Before I can talk about postmodernity, I need to establish where we’re coming from. And this means talking about the successes of modernism.

I mentioned in my introduction that I see the the Swedish company Ikea as representing the epitome of modernism. Ikea manages a seamless blend of form and function to channel the individual desires of millions of people into achieving the goals of the company.

This is ne of the greatest achievements of modernism: the ability to create large scale organisations dedicated to achieving a single goal.

Consider, for example, Henry Ford. Before his company revolutionised the industry, cars were manufactured by hand. With the introduction of the assembly line, each component was constructed or attached by one individual or team. The workers didn’t need to know how to build an entire car, but just how to do their assigned task over and over again. The efficiency gains were staggering. While a car had previously taken more than 12 man-hours to assemble, now it could be done in a mere ninety minutes.

But interestingly enough, the history of the production line goes back a long way before Henry Ford. In the early 19th century the British Navy needed to make over 100,000 wooden blocks a year to equip her ships, and all of them needed to be manufactured by hand by craftsmen. This process was dramatically overhauled by Marc Isambard Brunel, who designed a series of steam powered machines, each of which could perform one element of the block-making process. When working together, and operated by relatively unskilled labour, blocks could be manufactured with significantly improved quality and speed. This was the first production line in England, although the concept did not spread to other industries for decades.

The key features of this system, as with Ford’s, were a carefully designed manufacturing process and the assignment of simple, repetitive tasks to unskilled, interchangeable workers.

The other pioneers of this approach were armies. Prior to large corporations, armies were the only structure that organised on this scale, and with the same features. Armies have a hierarchical command structure, a single purpose, and make heavy use of interchangeable, low value units. Military education is a machine for producing soldiers. The individual soldier in a war does not need to see the big picture, or understand strategy, but merely needs to perform their assigned task correctly and efficiently. And if one, or a hundred, or ten thousand are killed, then they can be replaced with identically trained units. To the General, there is little difference between an infantryman and a gun carriage. I think of Napoleon as one of the foremost proponents of this approach, with his Levee en Masse, a startling ability to raise, train and equip vast armies, with which he could overwhelm the smaller professional armies of other European states.

These are some of the key characteristics of modernism: carefully designed processes, efficiencies of scale, and the use of interchangeable workers. And these characteristics were so successful that in the 20th century they spread out of the factory and into the office, the store, and the restaurant. Consider your local Tim Horton’s franchise, for example. Every Tim Horton’s in the country follows the same process for preparing a ham sandwich; each step has a fixed number of seconds allocated, and these times are printed directly above the food preparation area. A franchise, at it’s heart, is a set of carefully designed processes that can be run by interchangeable staff with minimum training.

These economies of scale have brought us affordable cars, quick service at the coffee shop, and many other impressive achievements. Killer diseases such as smallpox were eradicated through large scale, efficient vaccination programs. The introduction of city-wide sanitation infrastructure in London in the 19th century dramatically curtailed incidences of Cholera. And the Prussian education system, which emphasises a standardised curriculum and teacher training methodology, has been adopted worldwide.

So although in later articles I will outline modernisms darker side, I want to make clear that I do not see it as ‘bad’ or ‘good’. It is at it’s core a set of organisational tools. What we as a society choose to do with these tools is up to us.